Uh-oh, I hear you thinking. It’s going to be one of those ranty ones. Well, yes, it is, but I will try to make it quick and relatively painless. This post describes one of the easiest ways to improve your writing: know your crutch words. Every writer has one or two, those mushy words we use to get us to the next part of the sentence. As an editor, the one I see most often in a fiction manuscript is ‘headed’. ‘Turned’ is a close second.

Jefferson didn't like lobster, so he headed to the car. Victoria turned to face Clive before speaking. "I guess we should wait?" she asked.

These sentences tell us what’s happening, but they don’t show us. Now, no doubt you’ve heard the “show don’t tell” advice before, but how do you know when you’re doing it? Part of the key is to know what your crutch words are.

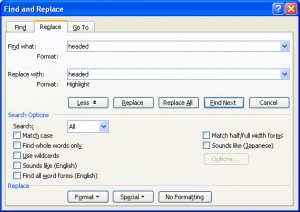

One way to do this is to use Microsoft Word’s Find feature. Try it on one of your manuscripts. If you check the Highlight all items found box, and select Main Document from the pull-down menu, then click Find All, this dialog box will give you a count of the number of times you’ve used the word ‘headed’ in your manuscript. If you’ve used a particular word (headed, back, just, said, turned) more than a couple-dozen times in a novel-length manuscript, my guess would be that at least a few of those instances could be revised away.

One way to do this is to use Microsoft Word’s Find feature. Try it on one of your manuscripts. If you check the Highlight all items found box, and select Main Document from the pull-down menu, then click Find All, this dialog box will give you a count of the number of times you’ve used the word ‘headed’ in your manuscript. If you’ve used a particular word (headed, back, just, said, turned) more than a couple-dozen times in a novel-length manuscript, my guess would be that at least a few of those instances could be revised away.

But wait, there’s more.

The highlight from this action only lasts until you close the Find dialog box. If you want to highlight these words semi-permanently, use the Replace feature.

First, choose a highlight color. Any color you like.

Then, call the Replace dialog. Fill it out like so:

The tricky part here is that you’re finding and replacing exactly the same word, but with the cursor in the Replace with text box, you’ll choose Format→Highlight. Then click Replace All. Every instance of the word ‘headed’ will be highlighted with the color you just chose.

Now you can see ’em… all those crutch words… and you can do something about them.

Like what?

With the example of Jefferson, who doesn’t like lobster, we already know what he’s doing, and why. The thing we would like to show here is how. Does Jeff stomp off to the car? Or does he hightail it, or slink surreptitiously, so that his hostess Evelyn won’t catch him, or does he scuttle to the parking lot (thus belaboring a crustacean-themed point)?

Jefferson scurried to his Buick. He had no idea a woman like Evelyn would serve lobster for breakfast.

The case with Victoria is slightly different. The bit of stage direction, when done well, can tell us a great deal about Victoria’s character, perceptions, attitudes (unlike the attempt I made in the example.) Here, we want to ask why. Why does Victoria turn away? Is she stalling for time, or trying to control her tears, because Clive can’t stand it when a woman cries, or is she simply revulsed by the sight of his double chins and those stupid Edwardian waistcoats he’s taken to wearing?

When we figure out why, the how usually follows. For example, if she’s trying not to cry, she might dip one shoulder lower than the other and hold her breath, or wrap her arm around her middle, or touch her manicured index fingers to the sides of her nose (especially if Clive is the one who paid for that rhinoplasty). If she’s revulsed, she might hold her body tense and her head slightly averted, and she might say the words to a point on the wall beyond Clive’s shoulder instead of looking him in the eyes.

Victoria recognized the futility of trying to converse with Clive before he'd been served his lunch. Instead, she focused on the mantelpiece behind him and spoke softly to herself. "I guess we'll just wait, then?"

See if you can turn your crutch words to your story’s advantage!